The Way Rebel Wilson's Team Reacted To Her Weight Loss Is A Sign of A Much Larger Problem In Hollywood - And America

By now, everybody knows about Rebel Wilson's incredible weight-loss journey - dubbed by the actress herself as her "year of health." It's been clear in every social media post and interview that Wilson was working very hard to get herself healthy, and that she feels great now that she has. But I don't want to talk about her weight loss right now - I want to talk about how her team reacted when she said she wanted to get healthy.

As she explained in a recent BBC interview, when Wilson announced to her PR team that she was going to do her year of health over the course of the pandemic, they reacted with shock, confusion, and trepidation.

"I got a lot of pushback from my own team actually here in Hollywood when I said, 'OK, I'm going to do this year of health. I feel like I'm really going to physically transform and change my life, and they were like, 'Why? Why would you want to do that?' Because I was earning millions of dollars being the funny fat girl and being that person."

Her team wanted her to stay "the funny fat girl" rather than risking her losing her niche in the film industry, despite the fact that Wilson wasn't doing this to make an aesthetic change - she was doing it because she knew that her emotional eating habits and lack of exercise were bad for her health, and she wanted to take better care of herself.

The people who made these comments, need I remind you, are the people who are supposed to be on her side: In Hollywood, an actor's team is there to help them get where THEY want to go. When Wilson said she wanted to lose weight, their next move should simply have been to support her in whatever way they could, and perhaps do some light PR about her transformation. Instead, they began agonizing over the possible death of her career. Why?

We put ourselves in boxes as humans, not just when it comes to casting, but all the time.

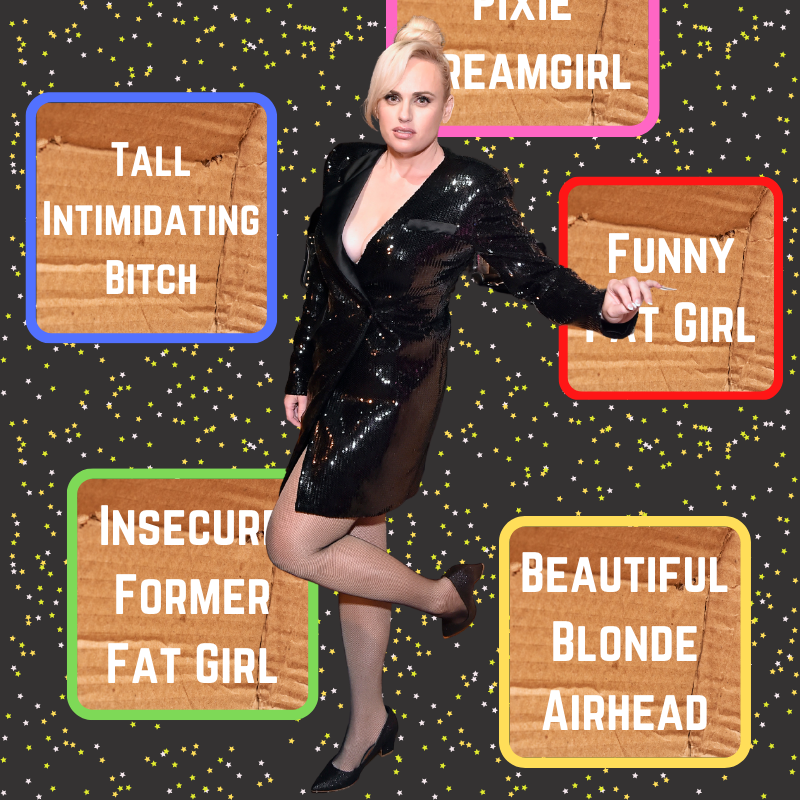

That was a rhetorical question. We know why. Hollywood operates on extremes: They love "average" when it means taking the averages of many people and making characters that can be cast with stock descriptions, like "beautiful blonde airhead" or "awkward nerdy dude" or "funny fat girl." They take the average and blow it up into a caricature-like extreme, leaving no room for things that are less "average" and more "normal." As long as they have the extremes that cover the spectrum, it doesn't matter if there isn't any overlap between personas, or people "in-between." (For example, Elle Woods as opposed to the stereotypical "dumb blonde" with no nuance.)

This is, of course, a generalization - to say all movies and TV shows do this would be reductive and dismissive of the efforts of thousands of people to change that culture - but the culture still stands, and everybody knows it. As Jack Donaghy on 30 Rock once put it:

"She needs to lose 30 pounds or gain 60. Anything in between has no place in television."

It doesn't matter who he was referring to - the fact that it was said at all is plenty.

We put ourselves in boxes as humans, not just when it comes to casting, but all the time. We use stereotypes to set expectations, and when people who look a certain way don't meet those stereotypes, we get confused (and perhaps even upset). And even when questions and comments that stem from that confusion are mostly benign, they still cause friction - at worst because they are dangerous, as assumptions made about people with darker skin often end in death or wrongful arrest - but even at their best, they pigeonhole people, assigning limits to people with great talent simply because they don't "look like the type."

Every new statistically significant population in this country has to take a turn in the stereotyping machine.

We're superficial. As people, it's how we are - and there's even a threadbare way that this argument makes sense, because oftentimes, people who look similar have similar ethnic and familial backgrounds, and those cultures can dictate a lot about how a person will act. Irish people (I say as an Irish person) do, in fact, tend to be able to hold their liquor, and take too long to tell a story. Italian people (I say as an Italian person) do, in fact, tend to talk with their hands, and use more garlic than the recipe recommends.

(I double it every time. Every time. Listen. You cannot trust any recipe to tell you how much garlic you need. The answer is inside of you.)

But this very threadbare argument is also the root of the problem, because these stereotypes are woven into the very fabric of America's (and, by extension, Hollywood and the filmmaking industry's,) history. We are a nation of colonizers and immigrants, and there are - unfortunately - very few communities left here who cannot trace their family history back to some trans-Atlantic or trans-Pacific crossing.

With each new wave of immigration into the US, new stereotypes emerged. The Irish were stereotyped as raucous, criminal drunks, and I was literally watching It's A Wonderful Life Last night and picked up on Italians being dismissively referred to as "garlic eaters" who need to be babysat. Every new statistically significant population in this country has to take a turn in the stereotyping machine, becoming the punching bag and the butt of the joke until a new group comes along - then they get to join in on the punching.

We do this because of base animal instinct - fear is there to protect us. It's normal to be suspicious of a new tribe when it comes along - in the early days of our species, if you weren't, it could get you killed. We stay afraid until there are positive stereotypes to model - one little orphan Annie actually had a big part in doing that for Irish people. When the populace finally had a little redheaded Irish girl, with all those stereotypical traits of impertinence and wiliness, that they could sympathize with rather than laugh at, the tides began to turn.

Now, however, the stereotypes are getting more and more abstract, and are rooted not only in xenophobia and racism but a host of other phobias and -isms that have even less bearing on what a person may be like - like fatphobia or homophobia.

It seems that people are now waking up to realize that the mirror we were looking into was a funhouse mirror.

It is an inalienable part of media's function in our society to create narratives around our lives. As the great Joan Didion once said:

"We tell ourselves stories in order to live."

Stories make the world make sense - and since oral tradition is no longer how we operate as a species, media is, by and large, how we tell those stories. It is, therefore, for better or for worse, part of the media's responsibility to make sure those stories - and the depictions of people within them - are actually still accurate, and not simply playing into existing stereotypes.

In the last century or so, television and movies have become a key part of that narrative formula - everybody watches TV. If you don't, it's weird - that is the prevailing attitude. We like them because they hold up a mirror to society, but it seems that people are now waking up to realize that the mirror we were looking into was a funhouse mirror. It distorted and enlarged some things, and made other things so small we can barely even see them.

This distortion is, in large part, due to the fact that the television industry has been fighting S&P (Standards and Practices) since the beginning. As we see in the new film about the making of I Love Lucy, Being The Ricardos, Lucille Ball had to fight just to have an episode where Lucy was pregnant. And why? Because the sensibilities of the 50's made us ashamed of sex and all things associated with it - and because the men in charge of Literally Every Company at the time were largely uncomfortable with women's bodies and how they worked.

The mirror has been manipulated, specifically, to attempt to show us in the most flattering light possible - and in that, it has exposed not only WHO is manipulating the mirror (because the picture that it's painting seems way more appealing to straight white guys than it would be to anyone else), but also the things that we find shameful as well. There's more to say in what we don't say than what we do, and that goes double when it comes to comedy, especially comedy centered around beauty standards.

Fat guys get gorgeous girls in media all the time. For a long time it seemed like the stock model for a sitcom was 'dopey fat guy married to high-strung and beautiful woman.' Conversely, the movies where a fat girl gets with a hot guy are almost invariably played as comedies.

Why? Why is that inherently funnier? And why doesn't Rebel Wilson's team think she can get those parts just as easily now that she is thinner?

Again, we know why. We know that the answer is supposed to be "because it goes against the norm - fat girls don't end up with guys, let alone hot guys." That's not a stock model for a couple that they can sell unless they pitch it as ironic. But nobody wants to say it out loud because we know, not only that it's mean, but that in real life, it's not at all accurate.

We are, essentially, handing people a fake brochure.

Media CREATES the social stereotypes we see simply by giving us exposure to them - it's a cycle that, because of their integral place in our public consciousness, can really only move forward with a majority of the professionals in the industry on board. (Social media has begun to help that roadblock by helping more people connect with others' stories, but until every generation in the working population is a social media native, that exposure effect won't be enough to turn the tide, and that's if the algorithms don't become too sophisticated first.)

And, yes, these stereotypes have their place in story and character development, as they are frequently based on very real and relatable traits - and if you remove yourself entirely from that cultural context, your show probably wouldn't resonate with many people anyway. But the professionals in the industry have to learn to let go of those stereotypes when they feel the tide turning, and many of them have not and still do not - and nothing represents that more clearly than the fact that Rebel Wilson's team, In The Body Positive Year Of Our Lord 2021, seemed so convinced that her worth as an actor was directly tied to her weight, instead of her talent.

Again: Why?

Unfortunately, it looks like the answer might just be "capitalism forces us to market everything." In the world we live in, what we watch is fed to us, now through more precise marketing campaigns than ever before. There is more data on people out there than ever, and marketers in entertainment - especially scripted entertainment - love to take that data, see what a certain group of people have in common, lump all of the most popular traits together, and present it to their audience saying, "look! This is a person like you, right? And we're going to cast that actor who reminds you of you in the role!"

We do this for the comfort of a familiar narrative. People don't like being wrong, or unable to read a situation, so many people become uncomfortable without stereotypes to lean on - or worse, when the stereotypes are changed, and they begin to misread things. And since TV's part in society is to show us examples of how "regular" people "like us" live their lives, when all the examples begin to look alike, many people - especially younger, more impressionable people, like teenagers - end up with a distorted idea of how real life is going to work. We are, essentially, handing people a fake brochure.

This creates a feedback loop of stereotyped information, and eventually it creates very specific, rigid boxes that we now feel we are expected to sort ourselves into - and then the companies, seeing us sort ourselves into neat, tidy little boxes, say "great! We know exactly how to market to you!"

They continue the feedback loop and intensify the problem, until we end up with gaping divides in how specific communities see and experience the world - and even differences in how we talk to each other and express humor. (Starting to sound familiar?)

America is full of these little micro-communities, and it always has been - and there are a lot more cultural differences between our micro-communities than there are in other countries, both due to our patchwork history and just the sheer size of the country.

Learning to communicate within the communities you're born into is usually second nature - you absorb it from the people around you and the media you consume. Learning to communicate outside your own micro-community, however, is a skill, and one that is actively weakened when we only see content that has been tailor-made for us - another factor that helps to perpetuate the funhouse mirror cycle.

The fact that people don't think it's a problem IS the problem.

It's also worth noting that this cycle puts an uneven amount of stress on communities of people who are different, be they people of color, disabled people, neurodivergent people, queer people, or another minority group. It places the burden of learning to communicate outside those micro-communities almost entirely on the already alienated minorities because otherwise, we can only speak to those within it about the struggles that are specific to us.

Most neurotypical people probably don't see many ads for shows about neurodivergence. Most white people probably don't see many ads for Black sitcoms. If they don't know about them, they can't watch them, and that actually matters more than we think it does.

There are those who may scoff at this concept - who may say that people should take it upon themselves to wake up and pay attention and resist what the media feeds them - but those people are missing the point.

We shouldn't HAVE to think this hard. If Hollywood was functioning ideally, the impressions we're getting would be more or less accurate to real life, and you wouldn't hear as many complaints as you do from those who feel underrepresented or unheard. The fact that people don't think it's a problem IS the problem - the "soft power" that these constructed identities have only works when nobody is paying attention to it. That is what makes it soft power - it only works in circumstances where public scrutiny is lax.

The rise of streaming services has helped with this - the new platforms are changing the game and hiring artists and creators who traditional broadcasting services have often overlooked, and they're telling new and less familiar stories that break the molds we've gotten so used to. Atypical is a show about boy with ASD and his family; Bridgerton race-bent their cast and used modern music and everyone ate it up (even though people in the business apparently never expected it to do so well); Insecure centers the experiences of people of color in a show people of ALL colors are loving.

Even still, as the algorithms for these services start to get to know their users better and become more complex, we run the risk of falling into the same trap again.

The actor's duty is to faithfully play a character on-screen, not to fill some stock role in the imaginary Popular Media Pantheon.

It's a natural cycle when it comes to business - they have a bottom line, and so they want to sell a reliable product. Up until recently, the whole industry has been honing reliable products to perfection - and the reaction of Rebel Wilson's team clearly shows that there are people high up in the business who don't know how to function without them, effectively proving that they've been using the same ones for a while.

What's worse is that the actor, for their part, is being taught how to brand themselves according to the boxes we've had forever - those ones that are so cliche you almost can't believe they're being used anymore, like "funny fat girl" or "sassy Black woman" or "dumb blonde" - and if they do something that goes against their personal brand, their PR team has to react.

Some - like Rebel Wilson's team, apparently - react very poorly, panicking about how the celebrity will "market themselves" once the change is made, as though they, the PR team, aren't supposed to be the ones in charge of that. The actor's duty is to faithfully play a character on-screen, not to fill some stock representative role in the imaginary Popular Media Pantheon. When we start to think of it as the reverse, we lose the very purpose of the shows and movies these actors play in in the first place.

Allison Jones is a fantastic casting director. Every show she casts, from Fresh Prince to The Office to What We Do In The Shadows, already has a leg up on the competition simply because of her skill at seeing into the soul of a role and finding an actor with the same one. She has filled some of the most iconic roles of our time - and she is so successful because she casts on performance and on spark, not on the tenuous concept of "does this person look the way we'd expect them to?"

When you set aside your expectations and just listen to the world around you, you end up with much more organic results - like the casting of David Wallace, the CEO of Dunder Mifflin in The Office. Andy Buckley was just some guy who auditioned who happened to work in finance for most of his life - but Jones saw that very specific Finance Guy aura, thought to herself 'this one will be perfect' and cast him instead of one of the established actors who auditioned - and the result was perfect.

Aaron Sorkin: looks just like Lucille Ball in costume

Aaron Sorkin: embodied the memory

We should not be slaves to the business of selling art.

All movies, all shows, all media, should be cast that way. It's the more honest way to do it. Any other method is contributing to all the problems I've outlined here: Rigid cults of personality, disjointedness in the way we communicate with one another, widespread personal image issues, and the dehumanization of actors in general. The bottom line? Don't focus on the surface-level stuff.

As tempting as it may be to make snap judgements and feel like you have the world figured out, we all gain much, much more from holding our tongues and LISTENING to one another - and Rebel Wilson's team should have LISTENED to what she wanted to do with HER body. She's not a clown there to do physical comedy or to be the butt of a joke just by showing up - she's an actor. She's there to play a whole person.

We should not be slaves to the business of selling art. Actors should not let the people who are in charge of promoting their art tell them how they should be making it - it is THEIR ART. Now that more artists have started pushing back about being honest about that, rather than making small sacrifices in the name of publicity, we're going to see those old stereotypes disappear - and hopefully, the ones that inevitably replace them won't stick around long enough to cause the same problems all over again.

© 2025 Enstarz.com All rights reserved. Do not reproduce without permission.